- Home

- L. Frank Baum

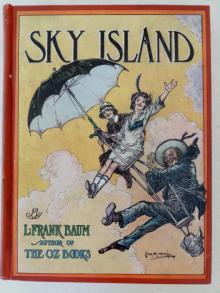

Sky Island Page 2

Sky Island Read online

Page 2

A MYSTERIOUS ARRIVAL

CHAPTER 1.

"Hello," said the boy.

"Hello," answered Trot, looking up surprised. "Where did you come from?"

"Philadelphia," said he.

"Dear me," said Trot; "you're a long way from home, then."

"'Bout as far as I can get, in this country," the boy replied, gazingout over the water. "Isn't this the Pacific Ocean?"

"Of course."

"Why of course?" he asked.

"Because it's the biggest lot of water in all the world."

"How do you know?"

"Cap'n Bill told me," she said.

"Who's Cap'n Bill?"

"An old sailorman who's a friend of mine. He lives at my house, too--thewhite house you see over there on the bluff."

"Oh; is that your home?"

"Yes," said Trot, proudly. "Isn't it pretty?"

"It's pretty small, seems to me," answered the boy.

"But it's big enough for mother and me, an' for Cap'n Bill," said Trot.

"Haven't you any father?"

"Yes, 'ndeed; Cap'n Griffith is my father; but he's gone, most of thetime, sailin' on his ship. You mus' be a stranger in these parts, littleboy, not to know 'bout Cap'n Griffith," she added, looking at her newacquaintance intently.

Trot wasn't very big herself, but the boy was not quite as big as Trot.He was thin, with a rather pale complexion and his blue eyes were roundand earnest. He wore a blouse waist, a short jacket and knickerbockers.Under his arm he held an old umbrella that was as tall as he was. Itscovering had once been of thick brown cloth, but the color had faded toa dull drab, except in the creases, and Trot thought it looked veryold-fashioned and common. The handle, though, was really curious. It wasof wood and carved to resemble an elephant's head. The long trunk of theelephant was curved to make a crook for the handle. The eyes of thebeast were small red stones, and it had two tiny tusks of ivory.

The boy's dress was rich and expensive, even to his fine silk stockingsand tan shoes; but the umbrella looked old and disreputable.

"It isn't the rainy season now," remarked Trot, with a smile.

The boy glanced at his umbrella and hugged it tighter.

"No," he said; "but umbrellas are good for other things 'sides rain."

"'Fraid of gett'n' sun-struck?" asked Trot.

He shook his head, still gazing far out over the water.

"I don't b'lieve this is bigger than any other ocean," said he. "I can'tsee any more of it than I can of the Atlantic."

"You'd find out, if you had to sail across it," she declared.

"When I was in Chicago I saw Lake Michigan," he went on dreamily, "andit looked just as big as this water does."

"Looks don't count, with oceans," she asserted. "Your eyes can only seejus' so far, whether you're lookin' at a pond or a great sea."

"Then it doesn't make any difference how big an ocean is," he replied."What are those buildings over there?" pointing to the right, along theshore of the bay.

"That's the town," said Trot. "Most of the people earn their living byfishing. The town is half a mile from here an' my house is almost a halfmile the other way; so it's 'bout a mile from my house to the town."

The boy sat down beside her on the flat rock.

"Do you like girls?" asked Trot, making room for him.

"Not very well," the boy replied. "Some of 'em are pretty good fellows,but not many. The girls with brothers are bossy, an' the girls withoutbrothers haven't any 'go' to 'em. But the world's full o' both kinds,and so I try to take 'em as they come. They can't help being girls, ofcourse. Do you like boys?"

"When they don't put on airs, or get rough-house," replied Trot. "My'sperience with boys is that they don't know much, but think they do."

"That's true," he answered. "I don't like boys much better than I dogirls; but some are all right, and--you seem to be one of 'em."

"Much obliged," laughed Trot. "You aren't so bad, either, an' if wedon't both turn out worse than we seem we ought to be friends."

He nodded, rather absently, and tossed a pebble into the water.

"Been to town?" he asked.

"Yes. Mother wanted some yarn from the store. She's knittin' Cap'n Billa stocking."

"Doesn't he wear but one?"

"That's all. Cap'n Bill has one wooden leg," she explained. "That's whyhe don't sailor any more. I'm glad of it, 'cause Cap'n Bill knowsev'rything. I s'pose he knows more than anyone else in all the world."

"Whew!" said the boy; "that's taking a good deal for granted. Aone-legged sailor can't know much."

"Why not?" asked Trot, a little indignantly. "Folks don't learn thingswith their legs, do they?"

"No; but they can't get around, without legs, to find out things."

"Cap'n Bill got 'round lively 'nough once, when he had two meat legs,"she said. "He's sailed to 'most ev'ry country on the earth, an' foundout all that the people in 'em knew, and a lot besides. He wasshipwrecked on a desert island, once, and another time a cannibal kingtried to boil him for dinner, an' one day a shark chased him sevenleagues through the water, an'--"

"What's a league?" asked the boy.

"It's a--a distance, like a mile is; but a league isn't a mile, youknow."

"What is it, then?"

"You'll have to ask Cap'n Bill; he knows ever'thing."

"Not ever'thing," objected the boy. "I know some things Cap'n Bill don'tknow."

"If you do you're pretty smart," said Trot.

"No; I'm not smart. Some folks think I'm stupid. I guess I am. But Iknow a few things that are wonderful. Cap'n Bill may know more'n I do--agood deal more--but I'm sure he can't know the same things. Say, what'syour name?"

"I'm Mayre Griffith; but ever'body calls me 'Trot.' It's a nickname Igot when I was a baby, 'cause I trotted so fast when I walked, an' itseems to stick. What's _your_ name?"

"Button-Bright."

"How did it happen?"

"How did what happen?"

"Such a funny name."

The boy scowled a little.

"Just like your own nickname happened," he answered gloomily. "My fatheronce said I was bright as a button, an' it made ever'body laugh. So theyalways call me Button-Bright."

"What's your real name?" she inquired.

"Saladin Paracelsus de Lambertine Evagne von Smith."

"Guess I'll call you Button-Bright," said Trot, sighing. "The only otherthing would be 'Salad,' an' I don't like salads. Don't you find it hardwork to 'member all of your name?"

"I don't try to," he said. "There's a lot more of it, but I've forgottenthe rest."

"Thank you," said Trot. "Oh, here comes Cap'n Bill!" as she glanced overher shoulder.

Button-Bright turned also and looked solemnly at the old sailor who camestumping along the path toward them. Cap'n Bill wasn't a very handsomeman. He was old, not very tall, somewhat stout and chubby, with a roundface, a bald head and a scraggly fringe of reddish whisker underneathhis chin. But his blue eyes were frank and merry and his smile like aray of sunshine. He wore a sailor shirt with a broad collar, a shortpeajacket and wide-bottomed sailor trousers, one leg of which coveredhis wooden limb but did not hide it. As he came "pegging" along thepath, as he himself described his hobbling walk, his hands were pushedinto his coat pockets, a pipe was in his mouth and his black neckscarfwas fluttering behind him in the breeze like a sable banner.

Button-Bright liked the sailor's looks. There was something verywinning--something jolly and care-free and honest and sociable--aboutthe ancient seaman that made him everybody's friend; so the strange boywas glad to meet him.

"Well, well, Trot," he said, coming up, "is this the way you hurry totown?"

"No, for I'm on my way back," said she. "I did hurry when I was going,Cap'n Bill, but on my way home I sat down here to rest an' watch thegulls--the gulls seem awful busy to-day, Cap'n Bill--an' then I foundthis boy."

Cap'n Bill looked at the boy curiously.

"Don't think as ever I sawr him

at the village," he remarked. "Guess asyou're a stranger, my lad."

Button-Bright nodded.

"Hain't walked the nine mile from the railroad station, hev ye?" askedCap'n Bill.

"No," said Button-Bright.

The sailor glanced around him.

"Don't see no waggin, er no autymob'l'," he added.

"No," said Button-Bright.

"Catch a ride wi' some one?"

Button-Bright shook his head.

"A boat can't land here; the rocks is too thick an' too sharp,"continued Cap'n Bill, peering down toward the foot of the bluff on whichthey sat and against which the waves broke in foam.

"No," said Button-Bright; "I didn't come by water."

Trot laughed.

"He must 'a' dropped from the sky, Cap'n Bill!" she exclaimed.

Button-Bright nodded, very seriously.

"That's it," he said.

"Oh; a airship, eh?" cried Cap'n Bill, in surprise. "I've hearn tell o'them sky keeridges; someth'n' like flyin' autymob'l's, ain't they?"

"I don't know," said Button-Bright; "I've never seen one."

Both Trot and Cap'n Bill now looked at the boy in astonishment.

"Now, then, lemme think a minute," said the sailor, reflectively."Here's a riddle for us to guess, Trot. He dropped from the sky, hesays, an' yet he did'nt come in a airship!

"'Riddlecum, riddlecum ree; What can the answer be?'"

Trot looked the boy over carefully. She didn't see any wings on him. Theonly queer thing about him was his big umbrella.

"Oh!" she said suddenly, clapping her hands together; "I know now."

"Do you?" asked Cap'n Bill, doubtfully. "Then you're some smarter ner Iam, mate."

"He sailed down with the umbrel!" she cried. "He used his umbrel as apara--para--"

"Shoot," said Cap'n Bill. "They're called parashoots, mate; but why, Ican't say. Did you drop down in that way, my lad?" he asked the boy.

"Yes," said Button-Bright; "that was the way."

"But how did you get up there?" asked Trot. "You had to get up in theair before you could drop down, an'--oh, Cap'n Bill! he says he's fromPhillydelfy, which is a big city way at the other end of America."

"Are you?" asked the sailor, surprised.

Button-Bright nodded again.

"I ought to tell you my story," he said, "and then you'd understand. ButI'm afraid you won't believe me, and--" he suddenly broke off and lookedtoward the white house in the distance--"Didn't you say you lived overthere?" he inquired.

"Yes," said Trot. "Won't you come home with us?"

"I'd like to," replied Button-Bright.

"All right; let's go, then," said the girl, jumping up.

The three walked silently along the path. The old sailorman had refilledhis pipe and lighted it again, and he smoked thoughtfully as he peggedalong beside the children.

"Know anyone around here?" he asked Button-Bright.

"No one but you two," said the boy, following after Trot, with hisumbrella tucked carefully underneath his arm.

"And you don't know us very well," remarked Cap'n Bill. "Seems to meyou're pretty young to be travelin' so far from home, an' amongstrangers; but I won't say anything more till we've heard your story.Then, if you need my advice, or Trot's advice--she's a wise little girl,fer her size, Trot is--we'll freely give it an' be glad to help you."

"Thank you," replied Button-Bright; "I need a lot of things, I'm sure,and p'raps advice is one of 'em."

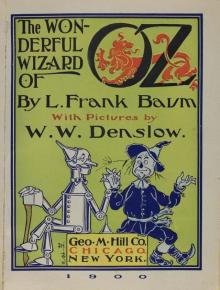

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

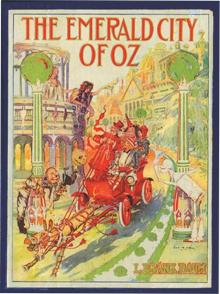

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz The Emerald City of Oz

The Emerald City of Oz The Story of Peter Pan, Retold from the fairy play by Sir James Barrie

The Story of Peter Pan, Retold from the fairy play by Sir James Barrie Sky Island

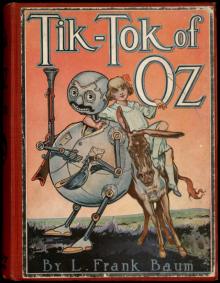

Sky Island Tik-Tok of Oz

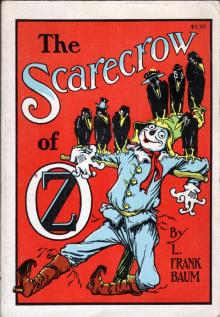

Tik-Tok of Oz The Scarecrow of Oz

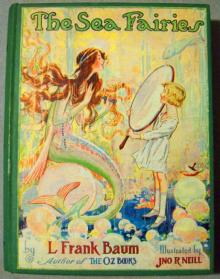

The Scarecrow of Oz The Sea Fairies

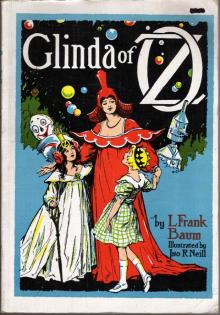

The Sea Fairies Glinda of Oz

Glinda of Oz The Lost Princess of Oz

The Lost Princess of Oz The Tin Woodman of Oz

The Tin Woodman of Oz Ozma of Oz

Ozma of Oz The Master Key

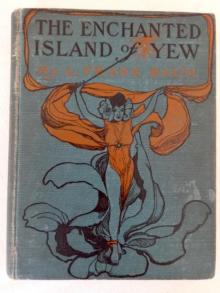

The Master Key The Enchanted Island of Yew

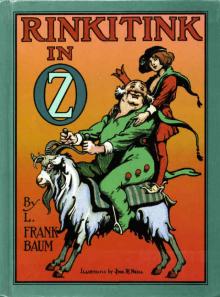

The Enchanted Island of Yew Rinkitink in Oz

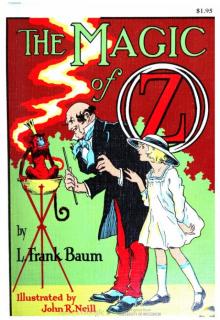

Rinkitink in Oz The Magic of Oz

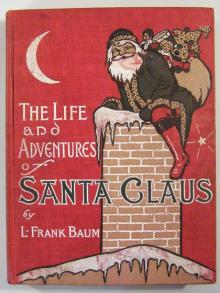

The Magic of Oz The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus

The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus The Marvelous Land of Oz

The Marvelous Land of Oz The Royal Book of Oz

The Royal Book of Oz The Road to Oz

The Road to Oz Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz

Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz The Patchwork Girl of Oz

The Patchwork Girl of Oz The Woggle-Bug Book

The Woggle-Bug Book Little Wizard Stories of Oz

Little Wizard Stories of Oz Yankee in Oz

Yankee in Oz Aunt Jane's Nieces and Uncle John

Aunt Jane's Nieces and Uncle John Mary Louise

Mary Louise Prairie-Dog Town

Prairie-Dog Town Aunt Jane's Nieces at Millville

Aunt Jane's Nieces at Millville John Dough and the Cherub

John Dough and the Cherub Aunt Jane's Nieces in Society

Aunt Jane's Nieces in Society Mary Louise in the Country

Mary Louise in the Country Aunt Jane's Nieces Abroad

Aunt Jane's Nieces Abroad Aunt Jane's Nieces at Work

Aunt Jane's Nieces at Work Aunt Jane's Nieces on the Ranch

Aunt Jane's Nieces on the Ranch Aunt Jane's Nieces in the Red Cross

Aunt Jane's Nieces in the Red Cross Dot and Tot of Merryland

Dot and Tot of Merryland Aunt Jane's Nieces on Vacation

Aunt Jane's Nieces on Vacation The Giant Horse Of Oz

The Giant Horse Of Oz The Hidden Valley of Oz

The Hidden Valley of Oz Mary Louise and the Liberty Girls

Mary Louise and the Liberty Girls Mary Louise Solves a Mystery

Mary Louise Solves a Mystery The Santa Claus Stories

The Santa Claus Stories Aunt Judith: The Story of a Loving Life

Aunt Judith: The Story of a Loving Life Aunt Jane's Nieces

Aunt Jane's Nieces Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Oz, The Complete Collection

Oz, The Complete Collection Complete Works of L. Frank Baum

Complete Works of L. Frank Baum The Wizard of Oz

The Wizard of Oz Oz 10 - Rinkitink in Oz

Oz 10 - Rinkitink in Oz