- Home

- L. Frank Baum

Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Read online

Table of Contents

From the Pages of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Title Page

Copyright Page

L. Frank Baum

The World of L. Frank Baum and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

The First American Children’s Book

Introduction

Dedication

Chapter I. - The Cyclone,

Chapter II. - The Council with The Munchkins.

Chapter III - How Dorothy saved the Scarecrow.

Chapter IV. - The Road through the Forest.

Chapter V. - The Rescue of the Tin Woodman<<<br />

Chapter VI. - The Cowardly Lion.

Chapter VII. - The Journey to The Great Oz.

Chapter VIII. - The Deadly Poppy Field.

Chapter IX. - The Queen of the Field Mice.

Chapter X. - The Guardian of the Gates.

Chapter XI. - The Wonderful Emerald City of OZ. Emerald City Oz.

Chapter XII. - Then 5carctv for the Wicked Witch.

Chapter XIII. - The Rescve

Chapter XIV. - The Winged Morvkeys

Chapter XV. - The Discovery of oz, The Terrible.

Chapter XVI. - The Magic Art of the Great Humbug.

Chapter XVII. - How the Ballo was Launched.

Chapter XVIII. - Away to the south.

Chapter XIX. - Attacked by the Fighting Trees.

Chapter XX. - ‘The Dainty China Country.

Chapter XXI. - The Lion Becomes The King of Beasts.

Chapter XXII. - The Country of the Quadlings

Chapter XXIII. - The Good Witch Grants Dorothy’s

Home Again.

Endnotes

Inspired by The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Comments & Questions

For Further Reading

From the Pages of

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

“You are welcome, most noble Sorceress, to the land of Munchkins. We are so grateful to you for having killed the wicked Witch of the East, and for setting our people free from bondage.” (page 22)

While Dorothy was looking earnestly into the queer, painted face of the Scarecrow, she was surprised to see one of the eyes slowly wink at her. She thought she must have been mistaken, at first, for none of the scarecrows in Kansas ever wink. (page 35)

“No matter how dreary and gray our homes are, we people of flesh and blood would rather live there than in any other country, be it ever so beautiful. There is no place like home.” (page 42)

“I shall take the heart,” returned the Tin Woodman; “for brains do not make one happy, and happiness is the best thing in the world.” (page 55)

“If you don’t mind, I’ll go with you,” said the Lion, “for my life is simply unbearable without a bit of courage.” (page 63)

They now came upon more and more of the big scarlet poppies, and fewer and fewer of the other flowers; and soon they found themselves in the midst of a great meadow of poppies. Now it is well known that when there are many of these flowers together their odor is so powerful that anyone who breathes it falls asleep, and if the sleeper is not carried away from the scent of the flowers he sleeps on and on forever. (pages 78-80)

“You killed the Witch of the East and you wear the silver shoes, which bear a powerful charm. There is now but one Wicked Witch left in all this land, and when you can tell me she is dead I will send you back to Kansas—but not before.” (pages 108-109)

This made Dorothy so very angry that she picked up the bucket of water that stood near and dashed it over the Witch, wetting her from head to foot. (page 127)

As the Monkey King finished his story Dorothy looked down and saw the green, shining walls of the Emerald City before them. She wondered at the rapid flight of the Monkeys, but was glad the journey was over. (page 144)

“I am Oz, the Great and Terrible,” said the little man, in a trembling voice, “but don’t strike me—please don’t!—and I’ll do anything you want me to.” (page 150)

“Can’t you give me brains?” asked the Scarecrow.

“You don’t need them. You are learning something every day. A baby has brains, but it doesn’t know much. Experience is the only thing that brings knowledge, and the longer you are on earth the more experience you are sure to get.” (page 154)

“But I don’t want to live here,” cried Dorothy. “I want to go to Kansas, and live with Aunt Em and Uncle Henry.” (page 174)

Dorothy said nothing. Oz had not kept the promise he made her, but he had done his best, so she forgave him. As he said, he was a good man, even if he was a bad Wizard. (page 182)

When they were all quite presentable they followed the soldier girl into a big room where the Witch Glinda sat upon a throne of rubies.

(page 207)

Dorothy now took Toto up solemnly in her arms, and having said one last good-bye she clapped the heels of her shoes together three times, saying, “Take me home to Aunt Em!” (page 211)

Published by Barnes & Noble Books

122 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10011

www.barnesandnoble.com/classics

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was first published in 1900.

Published in 2005 by Barnes & Noble Classics with new Introduction,

Notes, Biography, Chronology, Inspired By, Comments & Questions,

and For Further Reading.

Introduction, Notes, and For Further Reading

Copyright © 2005 by J. T. Barbarese.

Note on L. Frank Baum, The World of L. Frank Baum

and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Inspired by The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,

and Comments & Questions

Copyright © 2005 by Barnes & Noble, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,including photocopy, recording,

or any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior

written permission of the publisher.

Barnes & Noble Classics and the Barnes & Noble Classics

colophon are trademarks of Barnes & Noble, Inc.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

ISBN-13: 978-1-59308-221-5 ISBN-10: 1-59308-221-5

eISBN : 978-1-411-43355-7

LC Control Number 2005920760

Produced and published in conjunction with:

Fine Creative Media, Inc.

322 Eighth Avenue

New York, NY 10001

Michael J. Fine, President and Publisher

Printed in the United States of America

QM

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

FIRST PRINTING

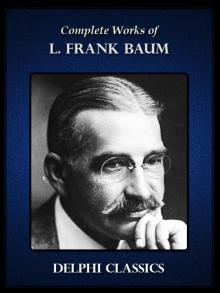

L. Frank Baum

When Lyman Frank Baum asked Maud Gage to marry him in 1882, the girl’s mother, a pioneering feminist, fiercely opposed the union. She apparently had good reason: The privileged son of a wealthy oilman, Baum led an itinerant life, uncertain of his future career; at the time, he was acting in a touring theatrical production funded by his father. Maud nevertheless went through with the marriage and found her husband to be a passionate, hardworking dreamer. Like his contemporary Mark Twain, Baum would reach the height of literary success only to have its fruits foiled by ill-timed and often fanciful investments.

If character was destiny for Baum, then early aspirations foretold a future in literature. Born in Chittenango, New York, in 1856, Frank spent his childhood on the Baum family estate, where he was given a printing press and created a family newspaper, the Rose Lawn Home Journal, with his brother. Despite a congenital heart ailment, Baum was quite active as a young m

an. He began writing professional newspaper articles, plays, poetry, and even a primer on breeding Hamburg chickens in the years following the American Civil War.

When his father and older brother died in 1887, the family’s fortunes declined, and Baum and his wife moved to Aberdeen in the Dakota Territory, where Maud’s brothers and sisters were living. Baum started a general store, Baum’s Bazaar, where local children gathered for candy and the imaginative stories Baum told for their entertainment. But their generous extensions of credit to drought-plagued ranchers and farmers forced the couple out of business in 1890. An ill-timed foray into newspaper editing and other publishing ventures left them bankrupt and poised for another move, this time to Chicago. To make ends meet, Frank worked as a reporter and, with good success, as a traveling salesman for the glassware company Pitkin and Brooks.

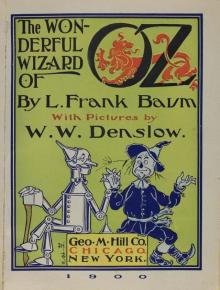

Although Baum’s four sons had long enjoyed their father’s fantastical stories, Baum did not publish his tales until Mother Goose in Prose appeared in 1897. Its success inspired Father Goose, His Book (1899), which was the best-selling children’s book of the year. But it was the story of a farm girl named Dorothy, first told to his sons and neighborhood children in 1898, that became an instant success and would endure as a perpetual classic. Published as The Wonderful Wizard of Oz in 1900, with illustrations by William Wallace Denslow, Baum’s tale flew out of stores and, when it was staged in 1902, sold out theaters from New York to Chicago.

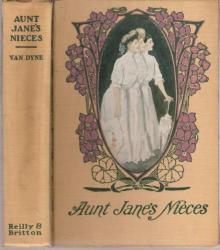

Thrilled by the novel’s reception, Baum wrote many sequels to the Oz story and enjoyed considerable financial success. But he also wanted to expand his repertoire beyond stories about Oz. His other books, some published under pen names, include Queen Zixi of Ix (1905), The Fate of a Crown (1905), and the teen series Aunt Jane’s Nieces (1906 through 1915). While these works enjoyed a healthy readership, failed business choices and his audience’s insatiable thirst for more Oz stories, kept him writing sequels until his death.

Always the devoted family man, Baum spent his final years living a quiet life in California. The grounds of his house (named Ozcot) were lush with Baum’s prize-winning flowers, which he cultivated until heart and gallbladder problems seriously threatened his health. Frank Baum died of a heart attack on May 6, 1919.

The World of L. Frank Baum and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

1856 Lyman Frank Baum is born on May 15 in Chittenango, New York, to Cynthia Stanton Baum and Benjamin Ward Baum. Having made a sizable fortune in oil and other busi ness ventures, Benjamin is able to raise his family of nine children in comfort.

1861 The American Civil War begins. Benjamin’s prospects con tinue to improve, allowing him to purchase a country man sion outside Syracuse, New York; called Rose Lawn, it has grounds large enough for young Frank to keep a flock of bantam chickens. Frank is a frail child, having been born with a heart ailment that will plague him into adulthood.

1865 The Civil War ends on April 9, and President Lincoln is as sassinated five days later.

1866 Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is pub lished. Baum will later be compared to Carroll because they both wrote about a young female protagonist.

1868 Frank is sent to Peekskill Military Academy; he loathes the school’s exacting discipline and schedule. Louisa May Al cott’s Little Women is published.

1870 Frank’s ill health allows him to leave Peekskill Military Academy.

1871 Early interests in writing and journalism lead Frank to cre ate a household newspaper, the Rose Lawn Home Journal.

1873 Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days is published.

1876 Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer is published.

1877 Baum begins writing professional journal articles and be comes involved in the theater.

1878 With high hopes for a stage career, he begins acting with the Union Square Theatre in Manhattan.

1882 Benjamin Baum funds a theater company for Frank, who writes his first play, The Maid of Arran. The production, with Frank in the lead role, enjoys some critical and com mercial success during its two-year run. Baum marries Maud Gage.

1883 Baum and Maud have a child, Frank Joslyn. Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island is published.

1884 Mismanagement and probable embezzlement by a book keeper cause the theater company to fold. Mark Twain’s Ad ventures of Huckleberry Finn appears.

1885 Baum sells Baum’s Castorine, an axle grease, for his family’s oil company.

1886 Baum writes his first book, The Book of Hamburgs, on the breeding and care of Hamburg chickens. Baum’s second son, Robert, is born.

1887 Benjamin Baum and his oldest son die. With the loss of the two competent Baum businessmen, the family’s income is greatly reduced. Frank and Maud Baum move to Aberdeen in the Dakota Territory, where they start a general store.

1890 Baum’s third son, Harry, is born. Baum’s store fails. Baum takes over as temporary editor of the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer, for which he writes articles and columns.

1891 Baum’s fourth son, Kenneth, is born. Almost penniless, Baum moves to Chicago, where he becomes a reporter for the Evening Post.

1892 Unable to support his family on the scant wages of a re porter, Baum also works as a traveling salesman for the chi naware company Pitkin and Brooks.

1893 The enormous World’s Columbian Exposition comes to Chicago. The United States experiences an economic de pression.

1894 Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book is published.

1897 Baum’s first children’s story, Mother Goose in Prose, is pub lished, with illustrations by Maxfield Parrish. Forced by ill health to give up selling, Baum founds Show Window, a journal on window trimming. The writer Opie Read intro duces Baum to William Denslow, who will later illustrate books by Baum.

1899 Father Goose, His Book, with illustrations by Denslow, is published by George M. Hill company. Its success—it sells more copies than any other children’s book this year—encourages Baum to continue writing. With extra money on hand, he buys a summerhouse in Macatawa Park, Michi gan, that he names the Sign of the Goose.

1900 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, with illustrations by Denslow, is published to resounding success. It has been in print ever since.

1901 Dot and Tot of Merryland, with illustrations by Denslow, is published.

1902 The Wizard of Oz is produced as a musical in Chicago and is sensationally popular. Baum splits with his illustrator William Denslow.

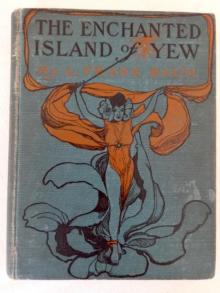

1903 The musical of The Wizard of Oz opens in New York. Baum tries to branch out by publishing the children’s book The Enchanted Island of Yew, but it has little success.

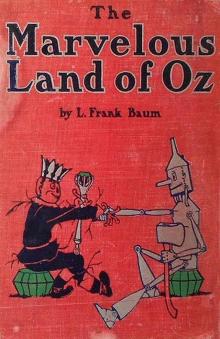

1904 Responding to high demand for another Oz tale, Baum publishes a second novel, The Marvelous Land of Oz.

1905 Queen Zixi of Ix is published. Determined to write other kinds of works, Baum publishes an adult romance, The Fate of a Crown, under the pseudonym Schuyler Staunton.

1906 Baum publishes Aunt Jane’s Nieces, the first of a series of ten novels written under the pen name Edith van Dyne.

1907 Ozma of Oz is published.

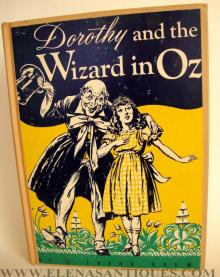

1908 Baum publishes Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz, in which he first calls himself the “Royal Historian of Oz.” His American Fairy Tales appears.

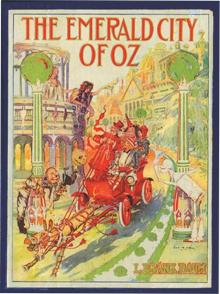

1910 Baum tries to end the Oz series with The Emerald City of Oz. The Baum family moves to California. Struggling with poor health, Baum oversees the building of a house he calls Ozcot.

1911 Peter and Wendy, J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan play in novel form, is published.

1913 Because Baum’s non-Oz books are not as successful as his Oz stories and he needs money, he writes The Patchwork Girl of Oz.

1914 Dreams of adapting his tales for film lead Baum to buy a

movie production company; but it fails after producing a handful of films. World War I begins.

1918 Coronary illness and gallbladder surgery lead to a protracted period of bed rest. Despite his failing health, Baum contin ues to write.

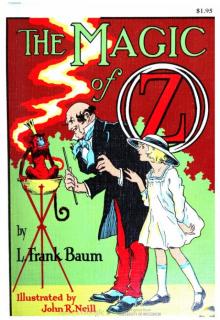

1919 Baum has a heart attack on May 5, shortly after The Magic of Oz is published. He d

ies within twenty-four hours.

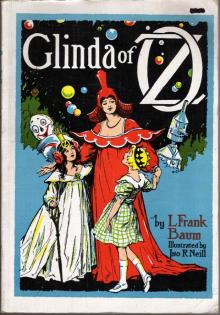

1920 Baum’s final Oz story, Glinda of Oz, is published. Ruth Plumly Thompson takes over as “Royal Historian of Oz.”

1939 MGM releases the classic film The Wizard of Oz, starring sixteen-year-old Judy Garland.

The First American

Children’s Book

The first thing that you notice is what Dorothy notices: Kansas is gray.

When Dorothy stood in the doorway and looked around, she could see nothing but the great gray prairie on every side. Not a tree nor a house broke the broad sweep of flat country that reached the edge of the sky in all directions. The sun had baked the plowed land into a gray mass, with little cracks running through it. Even the grass was not green, for the sun had burned the tops of the long blades until they were the same gray color to be seen everywhere. Once the house had been painted, but the sun blistered the paint and the rains washed it away, and now the house was as dull and gray as everything else (pp. 13-14).

Frank Baum was not the first to give Americans an American landscape in a children’s book. Twain had done it in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and even more radically in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), and Alcott had led out a suite of American pre-teens who grow into young adulthood with the March girls. But Twain and Alcott were writing juvenile books for a more mature audience. This book is Dorothy’s, and Dorothy is a child, in her own words, “a helpless girl” and clearly if indefinably younger than any host of a child’s narrative that Americans had encountered before 1900. We see Dorothy’s world through Dorothy’s eyes, a world constructed and policed, farmed and furnished by adults but modulated by a prose style that is childlike without being childish. In Dorothy, Baum gave America the first truly American child protagonist. 1

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz The Emerald City of Oz

The Emerald City of Oz The Story of Peter Pan, Retold from the fairy play by Sir James Barrie

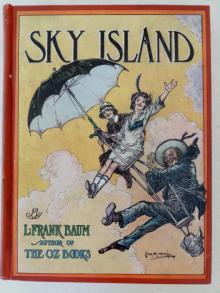

The Story of Peter Pan, Retold from the fairy play by Sir James Barrie Sky Island

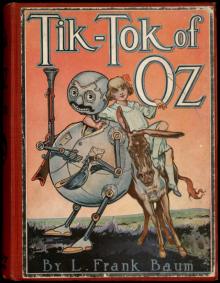

Sky Island Tik-Tok of Oz

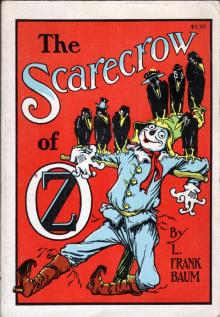

Tik-Tok of Oz The Scarecrow of Oz

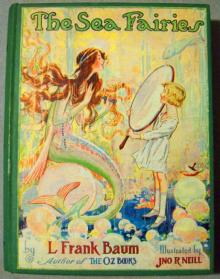

The Scarecrow of Oz The Sea Fairies

The Sea Fairies Glinda of Oz

Glinda of Oz The Lost Princess of Oz

The Lost Princess of Oz The Tin Woodman of Oz

The Tin Woodman of Oz Ozma of Oz

Ozma of Oz The Master Key

The Master Key The Enchanted Island of Yew

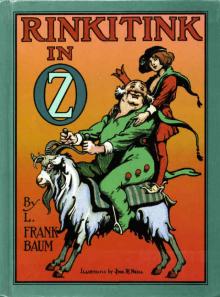

The Enchanted Island of Yew Rinkitink in Oz

Rinkitink in Oz The Magic of Oz

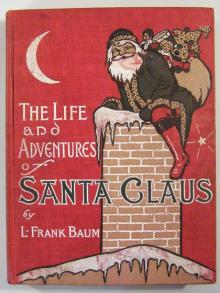

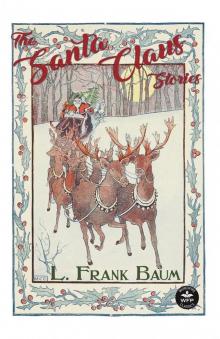

The Magic of Oz The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus

The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus The Marvelous Land of Oz

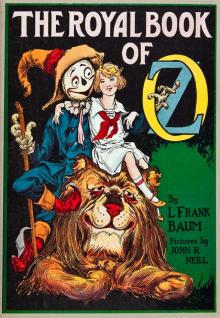

The Marvelous Land of Oz The Royal Book of Oz

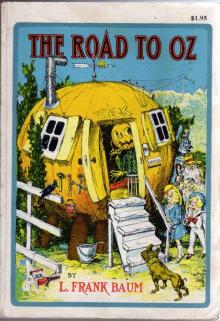

The Royal Book of Oz The Road to Oz

The Road to Oz Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz

Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz The Patchwork Girl of Oz

The Patchwork Girl of Oz The Woggle-Bug Book

The Woggle-Bug Book Little Wizard Stories of Oz

Little Wizard Stories of Oz Yankee in Oz

Yankee in Oz Aunt Jane's Nieces and Uncle John

Aunt Jane's Nieces and Uncle John Mary Louise

Mary Louise Prairie-Dog Town

Prairie-Dog Town Aunt Jane's Nieces at Millville

Aunt Jane's Nieces at Millville John Dough and the Cherub

John Dough and the Cherub Aunt Jane's Nieces in Society

Aunt Jane's Nieces in Society Mary Louise in the Country

Mary Louise in the Country Aunt Jane's Nieces Abroad

Aunt Jane's Nieces Abroad Aunt Jane's Nieces at Work

Aunt Jane's Nieces at Work Aunt Jane's Nieces on the Ranch

Aunt Jane's Nieces on the Ranch Aunt Jane's Nieces in the Red Cross

Aunt Jane's Nieces in the Red Cross Dot and Tot of Merryland

Dot and Tot of Merryland Aunt Jane's Nieces on Vacation

Aunt Jane's Nieces on Vacation The Giant Horse Of Oz

The Giant Horse Of Oz The Hidden Valley of Oz

The Hidden Valley of Oz Mary Louise and the Liberty Girls

Mary Louise and the Liberty Girls Mary Louise Solves a Mystery

Mary Louise Solves a Mystery The Santa Claus Stories

The Santa Claus Stories Aunt Judith: The Story of a Loving Life

Aunt Judith: The Story of a Loving Life Aunt Jane's Nieces

Aunt Jane's Nieces Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Oz, The Complete Collection

Oz, The Complete Collection Complete Works of L. Frank Baum

Complete Works of L. Frank Baum The Wizard of Oz

The Wizard of Oz Oz 10 - Rinkitink in Oz

Oz 10 - Rinkitink in Oz